African Journalism for Empire or Liberation I: Obstacles to starting a Black Newspaper

Via Goodblacknews.com

Today, African people are starved for robust new political voices and opinions. This was the same obstacle that the founding African journalists faced during the creation of the Freedom’s Journal. Today, it is as much the duty of the people as it is the duty of the publication to facilitate the people’s ideological development. The control over that development has shifted hands over the decades, first generating in Russwurm’s and Cornish’s, soon transitioning to more radical publications like Delany and Garvey’s and Briggs’ of the 1920s, and eventually the Black Press.

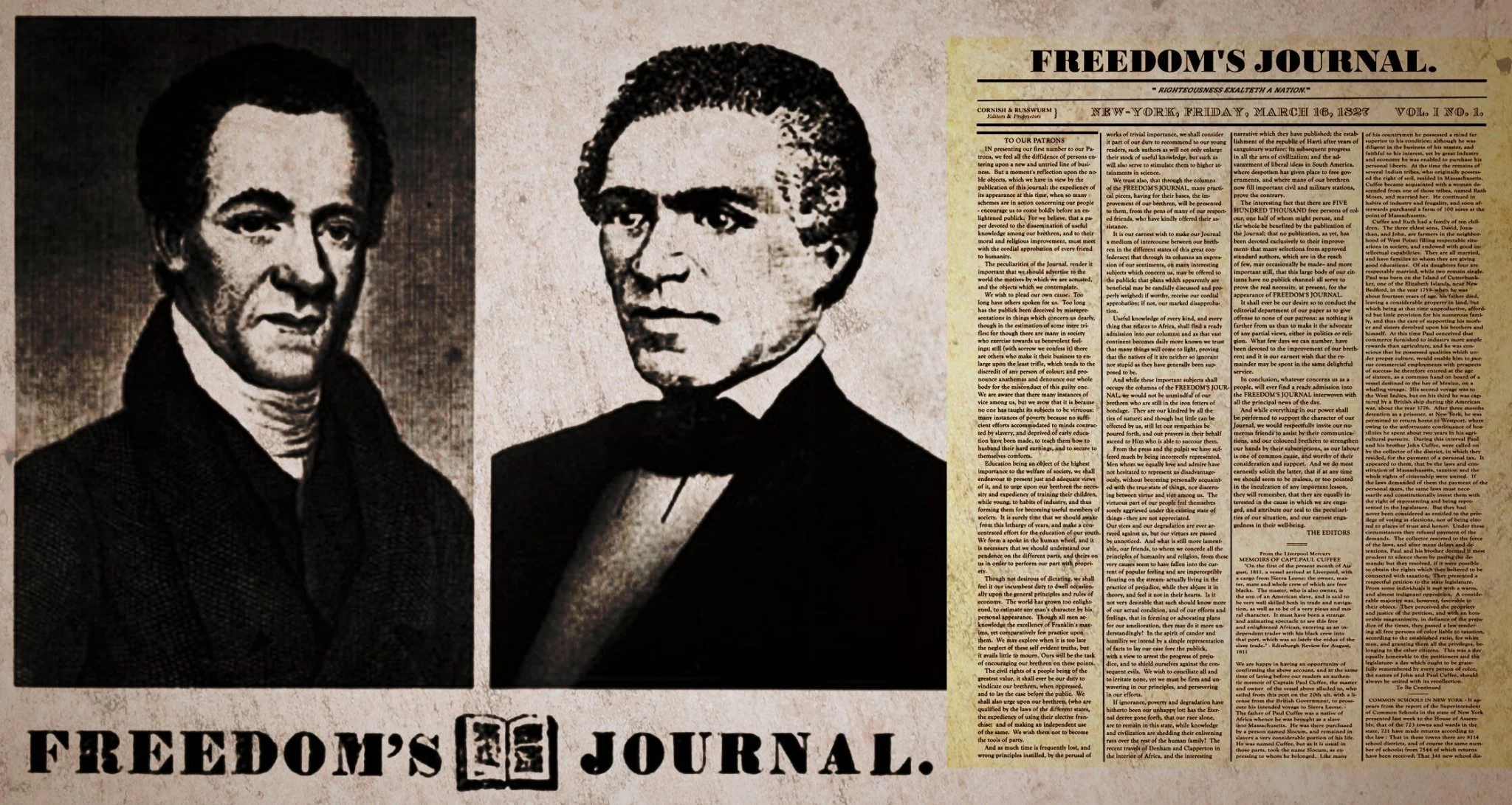

The history of African-owned (Black) Newspapers in the United States is closely aligned with the African (Black) radical tradition as it operates in the United States. The first African newspaper, The Freedom's Journal, served as a masterclass in the trials and tribulations of what starting and running an African newspaper in the United States is like. Founded in 1827, nearly 40 years before the abolishment of slavery, the Freedom's Journal set the class struggle as the presiding struggle for all subsequent African newspapers to reckon with in their respective times.

The Freedom's Journal was the beginning of an African (Black) press tradition that has since proven to transcend the institution of the Black press (National Newspaper Publisher Association), with new Black-owned publications not joining the NNPA and instead favoring their own innovative methods of journalism. The primary challenge that the Freedom's Journal faced was one of class struggle, which would touch all elements of publication, particularly its political framework, circulation hardship, and financial structure.

Samuel Cornish and John B. Russwurm were members of the free Black middle class in the North. Cornish was born in Delaware and was a graduate of the Free African School in Pennsylvania. Afterward, he co-founded the first Black Presbyterian church in Manhattan in 1822 (Blackpast). Russwurm was born in Jamaica to a wealthy European planter and an enslaved African, marking both his class status and his biracial status (Martin, H). His wealthy father moved to Maine in Russwurm's childhood and sent him to Quebec at age eight to gain an education (Bowdoin). Eventually, Russwurm became the third African to graduate from college in the United States.

Both Cornish and Russwurm met through their work in New York and brought together the Freedom's Journal, a journey that only lasted two years before its issues ground the paper's work to a halt. The principal issue that the paper faced was one of ideological struggle between the two founders, which largely stemmed from their socioeconomic class backgrounds and experiences resulting from it. Russwurm, being from Jamaica and born free, was equipped with a more intercommunalism perspective than his cofounder, Cornish, who was born free in America to natively born African parents. Cornish's political perspective was steeped in the African church tradition, as it evolved in the United States, so his perspective was largely rooted in a conservative, American-centric, and institutional framework.

It was both Cornish and Russwurm's political perspectives only materialized direct results of their socioeconomic class, which was free, black, and educated, while the mass majority of Africans in the United States were enslaved, illiterate, and abused. The access to capital and social upward mobility that Cornish and Russwurm had are also direct products of their socioeconomic class. The differences and similarities in their class backgrounds ultimately produced the very ideological struggle that ground Freedom's Journal to a halt in the first place. Russwurm wanted to support and receive support from the white-majority American Colonization Society, which he saw as a vehicle to promote African repatriation. On the other side, Cornish wanted to focus on African issues and advancement within the states and desired to continue relying on his clergy and Christian connections.

Cornish ultimately resigned in September 1827, leaving Russwurm to run the publication, and in no time, he was promoting African repatriation efforts along with the American Colonization Society. His political perspective warded off their current and prospective funders, which drove the publication into the ground and denied Russwurm the ability to effect change. Fundamentally, the mere presence of the ideological conflict that ended the publication was created only by their class backgrounds. The class struggle-produced political-ideological struggle would ultimately become a struggle that nearly every subsequent Black publication would have to reckon with. Soon after the Freedom's Journal, it was seen in the North Star between Frederick Douglass and Martin Delany; Douglass held a Cornish-aligned perspective for the destiny of Africans in the U.S., while Delany held -- almost verbatim -- a Russwurm-aligned repatriation perspective for the destiny of Africans in the U.S.

Today, Black publications both apart of the institutional Black Press or apart of the Black Press tradition are forced to choose at the outset which political perspective to fall into -- either one that's radical or one that's Christian-conservative. Both institutional and non-institutional Black publications also face the struggle of connecting to their readership, which originates in the Freedom's Journal's experiment with class struggle.

Both Russwurm and Cornish's economic backgrounds were instrumental in their individual, and eventually organizational, disconnection from the material reality of Africans in the United States, which led directly to the publication suffering in its circulation. The reality of the African material reality during the 1800s was a wretched reality -- the majority of Africans were in chains, illiterate, and kept uneducated. In contrast, European publications at the time had the full backing of European communities which allowed them to not only have a greater circulation but also to have a level of stability and reliability on their audience to help support their paper.

Initially the Freedom's Journal saw successes like its peak of 800 readers and a circulation that reached the likes of Haiti, Canada, and the United Kingdom (Partin). While explicit statistics on the demographics of the readership are largely unavailable, the publication still targeted Black readers and touted a Black readership. It wasn't until the political ideologies of both Cornish and Russwurm developed past the fundamental relationship of Africans to power, that the publication as a whole and their readership in particular began to decline.

After Cornish left and Russwurm aligned himself with the American Colonization Society -- a wealthy white majority organization -- the publication took a significant downturn because its middle-class black readership were not interested in Russwurm's middle-class rooted repatriation ideology. Repatriation, at that time, was reserved only for those who had the economic means to do so, who were willing to It was Russwurm's abandonment of the socio economic class status of his readers -- an abandonment only exacerbated by his own upward class mobility -- and favoring of a then-conservative White-led organization that led to the end of the publication under his direction.

Cornish, on the other hand, felt the need to ground himself among the communities of Africans in the United States and address the material needs there through a Christian lens. He did this in spite of his fast track on the pipeline to a middle class lifestyle, “both of his parents were free African Americans, Cornish was born free. After graduating from the Free African School in Philadelphia, Cornish began training to become a Presbyterian minister and was ordained in 1822” (Stirling). Cornish’s material praxis was extraordinary, and set a precedent for what African journalists and African publications should look towards when connecting with their people. Cornish himself kept African people at the center of the work he did while organizing churches and creating aid networks for Africans in New York. Cornish's only contradiction was his adherence to Christianity, which was not only rooted in classist politic, but also played a significant role in the financing, and lack thereof, of Freedom's Journal -- a financial struggle that would become part and parcel to the struggle of making a Black publication today.

The financial struggle of Freedom's Journal was more of a prophecy than a mere struggle. The publication's funding opportunities were significantly limited which even further limited their ability to run particular articles with particular slants/perspectives. Their primary source of funding was their readership base which they charged a $3.00 per year subscription fee for (Brittanica). That readership was alienated ideologically by Russwurm's direction exemplifying a class struggle that Russwurm would have to endure alone. Ultimately, relying on the free-black and conservative readership proved to be an unreliable financial structure for Freedom's Journal especially after Cornish's departure.

The class struggle on display in this instance is the struggle that African-owned publications have to endure against the owners of wealth and power, while trying to disseminate their messaging. Publications in the new age, however, have worked to reverse this challenge. The Baltimore Beat, for instance, produces a physical biweekly newspaper that is spread to Black communities across Baltimore -- their funding? The community. And not through mere readership either but through genuine communal attachment and connection by launching events that engage the people. The Beat holds its Summer Jam party which is a large fundraising opportunity that is supported by popular DJs. The Beat also holds community conversations biweekly so as to keep their readers and community engaged even while not actively publishing stories.

The Beat is not the only neo-Black press organization actively working to change the tide in the Black press either. The Kansas City Defender and Scalawag Magazine are both African-owned media publications in the South. Their missions are to help elevate the political consciousness of African communities in the South by covering government policies and reporting community hate crime stories that larger white publications often miss. For example, the Kansas City Defender -- ran by mostly young African people -- was the first publication to write about Ralph Yarl, a young African teen who was murdered by an old European man for mistakingly ringing his doorbell. They brought this story to the limelight and were able to garner national African support for the charging and indicting of the man who killed Yarl. The African press today is still paving the way for new African journalists to reach their communities.